Publius Vergilius Maro (October 15, 70 BCE – September 21, 19 BCE) was a classical Roman poet, better known by the Anglicised form of his name as Virgil or Vergil. His three major works are the Bucolics (or Eclogues), the Georgics and the Aeneid, although several minor poems are also attributed to him. The son of a farmer, he came to be regarded as one of Rome's greatest poets, and the Aeneid Rome's national epic.

Easton Press Virgil books

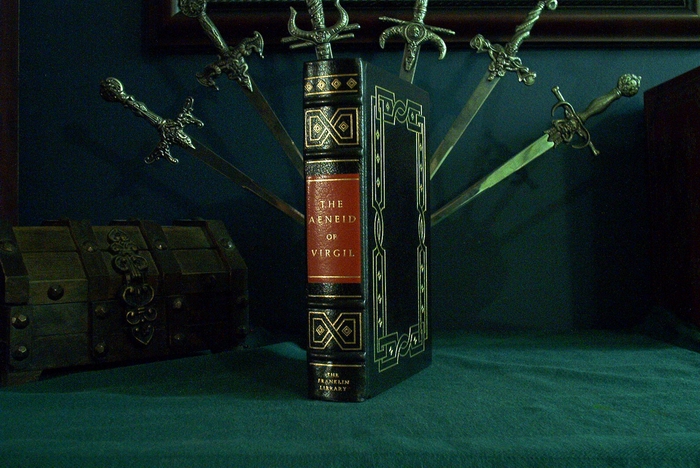

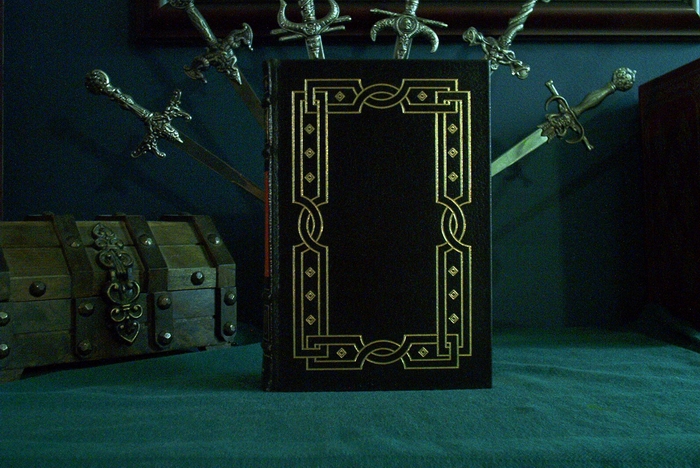

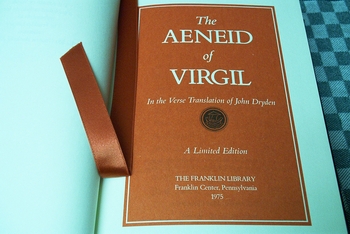

The Aeneid - 100 Greatest Books Ever Written - 1979Franklin Library Virgil books

The Aeneid - 100 Greatest Books of All Time - 1975The Eclogues and The Georgics - Great Books of the Western World - 1981

Virgil biography

Legend has it that Virgil was born in the village of Andes, near Mantua in Cisalpine Gaul. Scholars suggest Etruscan or Umbrian descent by examining the linguistic or ethnic markers of the region. Analysis of his name has led to beliefs that he descended from earlier Roman colonists. Modern speculation ultimately is not supported by narrative evidence either from his own writings or his later biographers. Etymological fancy has noted that his cognomen MARO shares its letters anagrammatically with the twin themes of his epic: AMOR (love) and ROMA (Rome).Legend also has it that Virgil received his first education when he was 5 years old and that he later went to Rome to study rhetoric, medicine, and astronomy, which he soon abandoned for philosophy; also that in this period, while in the school of Siro the Epicurean, he began to write poetry. A group of small works attributed to the youthful Virgil survive, but are largely considered spurious. One, the Catalepton, consists of fourteen short poems, some of which may be Virgil's, and another, a short narrative poem titled the Culex ("The Gnat"), was attributed to Virgil as early as the 1st century CE. These dubious poems are sometimes referred to as the Appendix Vergiliana.

During the civil strife that killed the Roman Republic, when Julius Caesar had been assassinated in 44 BCE, the army led by his assassins Brutus and Cassius met defeat by Caesar's faction, including his chief lieutenant Mark Antony and his newly adopted son Octavian Caesar in 42 BCE in Greece near Philippi. The victors paid off their soldiers with land expropriated from towns in northern Italy, supposedly including an estate near Mantua belonging to Virgil—again an inference from themes in his work and not supported by independent sources. Virgil dramatizes the contrasting feelings caused by the brutality of expropriation but also by the promise attaching to the youthful figure of Caesar's heir in the Bucolics in which he had worked out the mythic framework for lifelong ambition to conquer Greek epic for Rome.

In themes the ten eclogues develop and vary epic song, relating it first to Roman power (ecl. 1), then to love, both homosexual (ecl. 2) and panerotic (ecl. 3), then again to Roman power and Caesar's heir imagined as authorizing Virgil to surpass Greek epic and refound tradition (ecll. 4 and 5), shifting back to love then as a dynamic source considered apart from Rome (ecl. 6). Hence in the remaining eclogues Virgil withdraws from his newly minted Roman mythology and gradually constructs a new myth of his own poetics--he casts the remote Greek region of Arcadia, home of the god Pan, as the place of poetic origin itself. In passing, he again rings changes on erotic themes, such as requited and unrequited homosexual and heterosexual passion, tragic love for elusive women or magical powers of song to retrieve an elusive boy. He concludes by establishing Arcadia as a poetic ideal that still resonates in Western literature and visual arts.

Readers often did and sometimes do identify the poet himself with various characters and their vicissitudes, whether gratitude by an old rustic to a new god (ecl. 1), frustrated love by a rustic singer for a distant boy (his master's pet, ecl. 2), or a master singer's claim to have composed several eclogues (ecl. 5). Modern scholars largely reject such efforts to garner biographical details from fictive texts preferring instead to interpret the diverse characters and themes as representing the poet's own contrastive perceptions of contemporary life and thought.

Biographical reconstruction supposes that Virgil soon became part of the circle of Maecenas, Octavian's capable agent d'affaires who sought to counter sympathy for Mark Antony among the leading families by rallying Roman literary figures to Octavian's side. It also appears that Virgil gained many connections with other leading literary figures of the time, including Horace and Varius Rufus (who later helped finish the Aeneid). After he had completed the Bucolics (so-called in homage to Theocritus, who had been the first to write short epic poems taking herdsmen's life as their apparent theme — bucolic in Greek meaning "on care for cattle"), Virgil spent the ensuing years (perhaps 37–29 BCE) on the longer epic called Georgics (from Greek, "On Working the Earth", because farming is their apparent theme, in the tradition of Greek Hesiod), which he dedicated to Maecenas (source of the expression tempus fugit ["time flies"]). Virgil and Maecenas took turns reading the Georgics to Octavian upon his return from defeating Antony and his consort Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. In 27 BCE the Roman Senate conferred on Octavian the more than human title Augustus, well suited to Virgil's ambition to write an epic to challenge Homer, a Roman epic developed from the Caesarist mythology introduced in the Bucolics and incorporating now the Julian Caesars' family legend that traced their line back to a mythical Trojan prince who escaped the fall of Troy.

Final years and death

Virgil worked on the Aeneid during the last ten years of his life. Its first six books tell how the Trojan hero Aeneas escapes from the sacking of Troy and makes his way to Italy. On the voyage, a storm drives him to the coast of Carthage, which historically was Rome's deadliest foe. The queen, Dido, welcomes the ancestor of the Romans, and under the influence of the gods falls deeply in love with him. Jupiter recalls Aeneas to his duty towards Rome, however, and he slips away from Carthage, leaving Dido to commit suicide, cursing Aeneas and calling down revenge in a symbolic anticipation of the fierce wars between Carthage and Rome. On reaching Cumae, in Italy, Aeneas consults the Cumaean Sibyl, who conducts him through the Underworld and where Virgil imagines him meeting his father Anchises who reveals his son's Roman destiny to him.The six books (of "first writing") are modeled on Homer's Odyssey, but the last six are the Roman answer to the Iliad. Aeneas is betrothed to Lavinia, daughter of King Latinus, but Lavinia had already been promised to Turnus, the king of the Rutulians, who is roused to war by the Fury Allecto. The Aeneid ends with a single combat between Aeneas and Turnus, whom Aeneas defeats and kills, spurning his plea for mercy.

Virgil traveled with Augustus to Greece. En route, Virgil caught a fever, from which he died in Brundisium harbor, leaving the Aeneid unfinished. Augustus ordered Virgil's literary executors, Lucius Varius Rufus and Plotius Tucca, to disregard Virgil's own wish that the poem be burned, instead ordering it published with as few editorial changes as possible. As a result, the text of the Aeneid that exists may contain faults which Virgil was planning to correct before publication. However, the only obvious imperfections are a few lines of verse that are metrically unfinished (i.e., not a complete line of dactylic hexameter). Other alleged "imperfections" are subject to scholarly debate.

Incomplete or not, the Aeneid was immediately recognized as a masterpiece. It proclaimed the Imperial mission of the Roman Empire, while at the same time pitying Rome's victims and feeling their grief. Aeneas was considered to exemplify virtue and pietas (roughly translated as "piety", though the word is far more complex and has a sense of being duty-bound and respectful of divine will, family and homeland). Nevertheless, Aeneas struggles between doing what he wants as a man, and doing what he must as a virtuous hero. In the view of some modern critics, Aeneas' inner turmoil and shortcomings make him a more realistic character than the heroes of Homeric poetry, such as Odysseus.

The Eclogues

The biographical tradition asserts that Virgil began the hexameter Eclogues (or Bucolics) in 42 BC and it is thought that the collection was published around 39-38 BC, although this is controversial. The Eclogues (from the Greek for "selections") are a group of ten poems roughly modeled on the bucolic hexameter poetry ("pastoral poetry") of the Hellenistic poet Theocritus. After his victory in the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, fought against the army led by the assassins of Julius Caesar, Octavian tried to pay off his veterans with land expropriated from towns in northern Italy, supposedly including, according to the tradition, an estate near Mantua belonging to Virgil. The loss of his family farm and the attempt through poetic petitions to regain his property have traditionally been seen as Virgil's motives in the composition of the Eclogues. This is now thought to be an unsupported inference from interpretations of the Eclogues. In Eclogues 1 and 9, Virgil indeed dramatizes the contrasting feelings caused by the brutality of the land expropriations through pastoral idiom, but offers no indisputable evidence of the supposed biographic incident. Readers often did and sometimes do identify the poet himself with various characters and their vicissitudes, whether gratitude by an old rustic to a new god (Ecl. 1), frustrated love by a rustic singer for a distant boy (his master's pet, Ecl. 2), or a master singer's claim to have composed several eclogues (Ecl. 5). Modern scholars largely reject such efforts to garner biographical details from fictive texts preferring instead to interpret the diverse characters and themes as representing the poet's own contrastive perceptions of contemporary life and thought. Thematically, the ten Eclogues develop and vary pastoral tropes and play with generic expectations. 1 and 9 address the land confiscations and their effects on the Italian countryside. 2 and 3 are highly pastoral and erotic, discussing love, both homosexual (Ecl. 2) and panerotic (Ecl. 3). Eclogues 4, addressed to Asinius Pollio, the so-called 'Messianic Eclogue' uses the imagery of the golden-age in connection with the birth of a child (who the child is has been highly contested). 5 and 8 describe the myth of Daphnis in a song contest, 6, the cosmic and mythological song of Silenus, 7, a heated poetic contest, and 10 the sufferings of the contemporary elegiac poet Cornelius Gallus. Virgil is credited in the Eclogues with establishing Arcadia as a poetic ideal that still resonates in Western literature and visual arts and setting the stage for the development of Latin pastoral by Calpurnius Siculus, Nemesianus, and later writers.The Georgics

Sometime after the publication of the Eclogues (probably before 37 BC), Virgil became part of the circle of Maecenas, Octavian's capable agent d'affaires who sought to counter sympathy for Antony among the leading families by rallying Roman literary figures to Octavian's side. Virgil seems to have made connections with many of the other leading literary figures of the time, including Horace, in whose poetry he is often mentioned, and Varius Rufus, who later helped finish the Aeneid.At Maecenas' insistence (according to the tradition) Virgil spent the ensuing years (perhaps 37–29 BC) on the longer didactic hexameter poem called the Georgics (from Greek, "On Working the Earth") which he dedicated to Maecenas. The ostensible theme of the Georgics is instruction in the methods of running a farm. In handling this theme, Virgil follows in the didactic (instructive) tradition of the Greek poet Hesiod one of whose poems focuses on farming and the later Hellenistic poets. The four books of the Georgics focus respectively on raising crops and trees (1 and 2), livestock and horses (3), and beekeeping and the qualities of bees (4). Significant passages include the beloved Laus Italiae of Book 2, the prologue description of the temple in Book 3, and the description of the plague at the end of Book 3. Book 4 concludes with a long mythological narrative, in the form of an epyllion which describes vividly the discovery of beekeeping by Aristaeus and the story of Orpheus' journey to the underworld. Ancient scholars, such as Servius, conjectured that the Aristaeus episode replaced a long section in praise of Virgil's friend, the poet Gallus, who was disgraced by Augustus and committed suicide in 26 BC. Augustus is supposed to have ordered the section to be replaced.

A major critical issue in considering the Georgics is the assessment of tone; Virgil seems to waver between optimism and pessimism, sparking a great deal of debate on the poem's intentions. With the Georgics Virgil is again credited with laying the foundations for later didactic poetry. The biographical tradition says that Virgil and Maecenas took turns reading the Georgics to Octavian upon his return from defeating Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

The Aeneid of Virgil

The Aeneid by Virgil, the great national epic of Rome, composed between

the years 29 and 19 B.C. by the poet Publius Virgilius Maro, more

commonly known as Virgil. The epic was left without final revision upon

Virgil's death in 19 B.C. The Aeneid is a mythological work in twelve

books, describing the wanderings of the hero Aeneas and a small band of

Trojans after the fall of Troy. Aeneas escaped from Troy with the images

of his ancestral gods, carrying his aged father on his shoulders, and

leading is young son Ascanius by the hand, but in the confusion of his

hasty flight he lost his wife, Creusa. Having collected a fleet of

twenty vessels, he sailed with the surviving Trojans to Thrace, where he

began building a city. He subsequently abandoned his plan of a

settlement there and went to Crete, but was driven from the island by a

pestilence. After visiting Epirus, and Sicily, where his father died, he

was shipwrecked on the coast of Africa and welcomed by Dido, Queen of

Carthage. After a time he again set sail; Dido who had fallen in love

with him was heartbroken by his departure, and committed suicide. After

visiting Sicily again and stopping at Cumae, on the Bay of Naples, he

landed at the mouth of the Tiber River, seven years after the fall of

Troy, and there was welcomed by Latinus, King of Latium. Latvinia, the

daughter of Latinus, was destined to marry a stranger, but her mother

Amata had promised to give her in marriage to Turnus, King of the

Rutulians. A war ensued, which terminated with the defeat and death of

Ternus, thus making it possible the marriage of Aeneas and Lavinia.

Aeneas died three years later, and his son Ascanius founded Alba Longa,

the mother city of Rome.Virgil's Aeneid was highly appreciated in its own day. To judge from the fine quality of numerous manuscripts dating from the 3rd to the 5th century A.D., and the numerous references by later Roman writers, the Aeneid was popular for along time after its composition. During the Middle Ages hidden philosophical meanings were read into the poem, and Virgil himself was thought to be a seer and a magician. The importance of the Aeneid in the history of English poetry has been considerable. The English poet Geoffrey Chaucer told part of the story in his House of Fame. Edmund Spenser, in The Faerie Queene, was indebted to Virgil's conception of the epic as a national poem. The style and technique of versification practiced by such poets as John Milton and Alfred, Lord Tennyson were influenced by the Latin of Virgil's Aeneid. The work has been in widespread use a school text for centuries. Notable translations of the poem include those by John Dryden, William Morris, and Cecil Day Lewis.

Later views of Virgil

Even as the Roman empire collapsed, literate men acknowledged that the Christianized Virgil was a master poet. Gregory of Tours read Virgil, whom he quotes in several places, along with some other Latin poets, though he cautions that "we ought not to relate their lying fables, lest we fall under sentence of eternal death". The Aeneid remained the central Latin literary text of the Middle Ages and retained its status as the grand epic of the Latin peoples, and of those who considered themselves to be of Roman provenance, such as the English. It also held religious importance as it describes the founding of the Holy City. Virgil was made palatable for his Christian audience also through a belief in his prophecy of Christ in his Fourth Eclogue. Cicero and other classical writers too were declared Christian due to similarities in moral thinking to Christianity. Surviving medieval collections of manuscripts containing Virgil's works include the Vergilius Augusteus, the Vergilius Vaticanus and the Vergilius Romanus.

Dante made Virgil his guide to Hell and the greater part of Purgatory in The Divine Comedy. Dante also mentions Virgil in De vulgari eloquentia, along with Ovid, Lucan and Statius, as one of the four regulati poetae (ii, vi, 7).

Virgil continues to be considered one of the greatest Latin poets.

Virgil's tomb

The tomb known as "Virgil's tomb" is found at the entrance of an ancient Roman tunnel (also known as "grotta vecchia") in the Parco di Virgilio in Piedigrotta, a district two miles from old Naples, near the Mergellina harbor, on the road heading north along the coast to Pozzuoli. The site called Parco Virgiliano is some distance further north along the coast. While Virgil was already the object of literary admiration and veneration before his death, in the following centuries his name became associated with miraculous powers, his tomb the destination of pilgrimages and veneration. The poet himself was said to have created the cave with the fierce power of his intense gaze.

It is said that the Chiesa della Santa Maria di Piedigrotta was erected by Church authorities to neutralize this adoration and "Christianize" the site. The tomb, however, is a tourist attraction, and still sports a tripod burner originally dedicated to Apollo, bearing witness to the beliefs held by Virgil.

Virgil name

In the Middle Ages Vergilius was frequently spelled Virgilius. There are two explanations commonly given for this alteration. One educes a false etymology associated with the word virgo ("maiden" in Latin) due to Virgil's excessively "maiden"-like (parthenias or παρθηνιας in Greek) modesty. Alternatively, some argue that Vergilius was altered to Virgilius by analogy with the Latin virga ("wand") due to the magical or prophetic powers attributed to Virgil in the Middle Ages. In an attempt to reconcile his non-Christian background with the high regard in which medieval scholars held him, it was posited that some of his works metaphorically foretold the coming of Christ, hence making him a prophet of sorts. This view is defended by some scholars today, namely Richard F. Thomas of Harvard.

In Norman schools (following the French practice), the habit was to anglicize Latin names by dropping their Latin endings, hence Virgil.

In the 19th century, some German-trained classicists in the United States suggested modification to Vergil, as it is closer to his original name, and is also the traditional German spelling. Modern usage permits both, though the Oxford guide to style recommends Vergilius to avoid confusion with the 8th-century Irish grammarian Virgilius Maro Grammaticus.

Some post-Renaissance writers liked to affect the sobriquet "The Swan of Mantua".

Virgil quotes

"Fortune sides with him who dares." (Latin: "Audentes fortuna iuvat.")

"Love conquers all; let us too surrender to love." (Latin: "Amor vincit omnia; et nos cedamus amori.")

"Perhaps one day it will be pleasant to remember even this." (Latin: "Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.")

"Do not yield to evil, but attack it boldly." (Latin: "Neque enim levia aut ludicra petuntur / praemia, sed duris doloribus adiungitur auctor / exercitus.")

"The greatest wealth is health." (Latin: "Mens sana in corpore sano.")

"Death twitches my ear; 'Live,' he says... 'I am coming.'" (Latin: "Fugit hora; carpe diem; quam minimum credula postero.")

"Love is a kind of warfare." (Latin: "Amor omnibus idem.")

"Believe one who has proved it. Believe an expert." (Latin: "Fidem qui per has, duxit, non repperit, uni.")

Source and additional information: Virgil