Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was one of the most influential American writers of the 20th century. He wrote such works as Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), Cat's Cradle (1963), and Breakfast of Champions (1973) blending satire, black comedy, and science fiction. He was known for his humanist beliefs and was honorary president of the American Humanist Association.

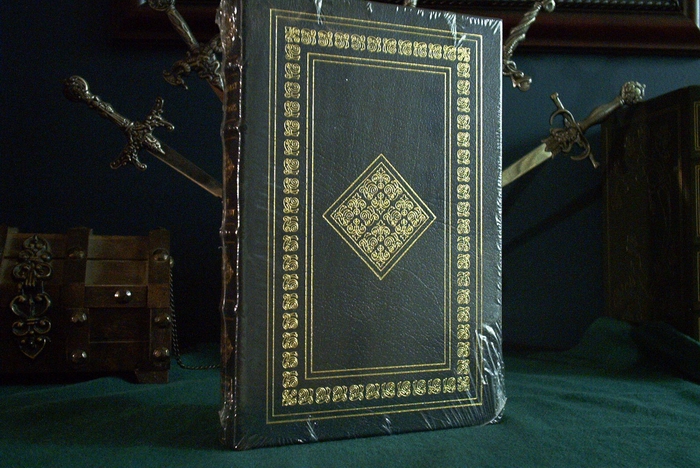

Easton Press Kurt Vonnegut books

Timequake - signed first edition - 1997

Slaughterhouse Five - signed modern classic - 1998

Bagombo Snuff Box - signed first edition (numbered 1700 copies) - 1999

God Bless you Dr Kevorkian - signed limited edition - 2000

Cat's Cradle - signed limited edition - 2000

Breakfast of Champions - signed limited edition - 2001

Slaughterhouse Five - The Great Books of The 20th Century - 2001

Mother Night - signed limited edition - 2003

God Bless you Mr Rosewater - signed limited edition - 2003

Welcome to the Monkey House - signed limited edition - 2003

Player Piano - signed limited edition - 2004

Slapstick - signed limited edition - 2004

A Man Without A Country - signed limited edition - 2005

Blue Beard - signed limited edition - 2005

Galapagos - signed limited edition - 2005

While Mortals Sleep - signed first edition - 2010

Look at The Birdie - signed first edition - 2010

Slaughterhouse Five - signed limited edition - 2011 (limited to 850 in slip case)

Franklin Library Kurt Vonnegut books

Slapstick - limited first edition (not signed) - 1976Jailbird - limited first edition (not signed) - 1979

Welcome to the Monkey House - worlds greatest writers - 1981

Galapagos - signed first edition - 1985

Blue Beard - signed first edition - 1987

Hocus Pocus - signed first edition - 1990

Author Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut was born to fourth-generation German-American parents, son and grandson of architects in the Indianapolis firm Vonnegut & Bohn, on Armistice Day. As a student at Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, Vonnegut worked on the nation's first daily high school newspaper, The Daily Echo. He attended Cornell University from 1941 to 1942, where he served as assistant managing editor and associate editor for the student newspaper, the Cornell Daily Sun, and majored in biochemistry. While attending Cornell, he was a member of the Delta Upsilon Fraternity, following in the footsteps of his father. While at Cornell, Vonnegut enlisted in the U.S. Army. The army sent him to the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and the University of Tennessee to study mechanical engineering. On May 14, 1944, Mothers' Day, his mother, Edith S. (Lieber) Vonnegut, committed suicide. World War II and the firebombing of Dresden

Kurt Vonnegut's experience as a soldier and prisoner of war had a profound influence on his later work. As a Corporal with the 106th Infantry Division, Vonnegut was cut off from his battalion and wandered alone behind enemy lines for several days until captured by Wehrmacht troops on December 14, 1944. Imprisoned in Dresden, Vonnegut witnessed the fire bombing of Dresden in February 1945, which destroyed most of the city. Vonnegut was one of just seven American prisoners of war in Dresden to survive, in their cell in an underground meat locker of a Slaughterhouse that had been converted to a prison camp. The administration building had the postal address Schlachthof Fünf (Slaughterhouse Five) which the prisoners took to using as the name for the whole camp. "Utter destruction", he recalled, "carnage unfathomable." The Germans put him to work gathering bodies for mass burial. "But there were too many corpses to bury. So instead the Nazis sent in troops with flamethrowers. All these civilians' remains were burned to ashes." This experience formed the core of one of his most famous works, Slaughterhouse-Five, and is a theme in at least six other books.Vonnegut was freed by Red Army troops in May 1945. Upon returning to America, he was awarded a Purple Heart for what he called a "ludicrously negligible wound," later writing in Timequake that he was given the decoration after suffering a case of "frostbite."

Post-war

After the war, Vonnegut attended the University of Chicago as a graduate student in anthropology and also worked as a police reporter at the City News Bureau of Chicago. According to Vonnegut in Bagombo Snuff Box, the university rejected his first thesis on the necessity of accounting for the similarities between Cubist painters and the leaders of late 19th century Native American uprisings, saying it was "unprofessional." He left Chicago to work in Schenectady, New York, in public relations for General Electric. The University of Chicago later accepted his novel Cat's Cradle as his thesis, citing its anthropological content and awarded him the M.A. degree in 1971.On the verge of abandoning writing, Vonnegut was offered a teaching job at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. While he was there, Cat's Cradle became a best-seller, and he began Slaughterhouse-Five, now considered one of the best American novels of the 20th century, appearing on the 100 best lists of Time magazine and the Modern Library.

Early in his adult life, he moved to Barnstable, Massachusetts, a town on Cape Cod.

Personal life

The author was known as Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., until his father's death in October 1957; after that he was known simply as Kurt Vonnegut. He was also the younger brother of Bernard Vonnegut, an atmospheric scientist who discovered that silver iodide could be used for cloud seeding, the process of artificial stimulation of rain.He married his childhood sweetheart, Jane Marie Cox, after returning from World War II, but the couple separated in 1970. He did not divorce Cox until 1979, but from 1970 Vonnegut lived with the woman who would later become his second wife, photographer Jill Krementz. Krementz and Vonnegut were married after the divorce from Cox was finalized.

He had seven children: three with his first wife, three more born to his sister Alice and adopted by Vonnegut after she died of cancer, and a seventh, Lily, adopted with Krementz. Two of these children have published books, including his only biological son, Mark Vonnegut, who wrote The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity, about his experiences in the late 1960s and his major psychotic breakdown and recovery; the tendency to insanity he acknowledged may be partly hereditary, influencing him to take up the study of medicine and orthomolecular psychiatry. Mark was named after Mark Twain, whom Vonnegut considered an American saint.

His daughter Edith ("Edie"), an artist, has also had her work published in a book titled Domestic Goddesses. She was once married to Geraldo Rivera. She was named after Kurt Vonnegut's mother, Edith Lieber. His youngest daughter is Nanette ("Nanny"), named after Nanette Schnull, Vonnegut's paternal grandmother. She is married to realist painter Scott Prior and is the subject of several of his paintings, notably "Nanny and Rose".

Of Vonnegut's four adopted children, three are his nephews: James, Steven, and Kurt Adams; the fourth is Lily, a girl he adopted as an infant in 1982. James, Steven, and Kurt were adopted after a traumatic week in 1958, in which their father was killed when his commuter train went off an open drawbridge in New Jersey, and their mother — Kurt's sister Alice — died of cancer. In Slapstick, or Lonesome No More!, Vonnegut recounts that Alice's husband died two days before Alice herself. Her family tried to hide the knowledge from her, but she found out when an ambulatory patient gave her a copy of the New York Daily News, a day before she herself died. The fourth and youngest of the boys, Peter Nice, went to live with a first cousin of their father in Birmingham, Alabama as an infant. Lily is a singer and actress.

On November 11, 1999, the asteroid 25399 Vonnegut was named in Vonnegut's honor.

On January 31, 2001, a fire destroyed the top story of his home. Vonnegut suffered smoke inhalation and was hospitalized in critical condition for four days. He survived, but his personal archives were destroyed. After leaving the hospital, he recuperated in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Vonnegut reportedly smoked Pall Mall cigarettes, unfiltered, which he claimed is a "classy way to commit suicide."

Death

Vonnegut died at the age of 84 on April 11, 2007, in Manhattan after a fall at his Manhattan home several weeks prior resulted in irreversible brain injuries.Writing career

Vonnegut's

first short story, "Report on the Barnhouse Effect" appeared in 1950 in

Collier's. His first novel was the dystopian novel Player Piano (1952),

in which human workers have been largely replaced by machines. He

continued to write short stories before his second novel, The Sirens of

Titan, was published in 1959. Through the 1960s, the form of his work

changed, from the relatively orthodox structure of Cat's Cradle (which

in 1971 earned him a master's degree) to the acclaimed,

semiautobiographical Slaughterhouse-Five, given a more experimental

structure by using time travel as a plot device.

These structural

experiments were continued in Breakfast of Champions (1973), which

included many rough illustrations, lengthy non-sequiturs and an

appearance by the author himself, as a deus ex machina.

"This is a very bad book you're writing," I said to myself.

"I know," I said.

"You're afraid you'll kill yourself the way your mother did," I said.

"I know," I said.

Vonnegut attempted suicide in 1984 and later wrote about this in several essays.

Breakfast

of Champions became one of his best-selling novels. It includes, in

addition to the author himself, several of Vonnegut's recurring

characters. One of them, science fiction author Kilgore Trout, plays a

major role and interacts with the author's character.

In addition

to recurring characters, there are also recurring themes and ideas. One

of them is ice-nine (a central wampeter in his novel Cat's Cradle),

said to be a new form of ice with a different crystal structure from

normal ice. When a crystal of ice-nine is brought into contact with

liquid water, it becomes a seed that "teaches" the molecules of liquid

water to arrange themselves into ice-nine. This process is not easily

reversible, however, as the melting point of ice-nine is 114.4 degrees

Fahrenheit (45.8 degrees Celsius).

Metaphorically, ice-nine

represents any potentially lethal invention created without regard for

the consequences. Ice-nine is patently dangerous, as even a small piece

of it dropped in the ocean would cause all the earth's water to

solidify. Yet it was created, simply because human beings like to create

and invent.

Although many of his novels involved science fiction

themes, they were widely read and reviewed outside the field, not least

due to their anti-authoritarianism. For example, his seminal short

story Harrison Bergeron graphically demonstrates how an ethos like

egalitarianism, when combined with too much authority, engenders

horrific repression.

In much of his work, Vonnegut's own voice is

apparent, often filtered through the character of science fiction

author Kilgore Trout (whose name is based on that of real-life science

fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon), characterized by wild leaps of

imagination and a deep cynicism, tempered by humanism. In the foreword

to Breakfast of Champions, Vonnegut wrote that as a child, he saw men

with locomotor ataxia, and it struck him that these men walked like

broken machines; it followed that healthy people were working machines,

suggesting that humans are helpless prisoners of determinism. Vonnegut

also explored this theme in Slaughterhouse-Five, in which protagonist

Billy Pilgrim "has come unstuck in time" and has so little control over

his own life that he cannot even predict which part of it he will be

living through from minute to minute. Vonnegut's well-known phrase "So

it goes", used ironically in reference to death, also originated in

Slaughterhouse-Five and became a slogan for anti-Vietnam War protestors

in the 1960s. "Its combination of simplicity, irony, and rue is very

much in the Vonnegut vein."

With the publication of his novel

Timequake in 1997, Vonnegut announced his retirement from writing

fiction. He continued to write for the magazine In These Times, where he

was a senior editor,[24] until his death in 2007, focusing on subjects

ranging from contemporary U.S. politics to simple observational pieces

on topics such as a trip to the post office. In 2005, many of his essays

were collected in a new bestselling book titled A Man Without a

Country, which he insisted would be his last contribution to letters.

His

“trip to the post office” is a Vonnegut-style discourse on what is lost

by a hermetically-isolated click of [send] on an e-mail. In a Luddite

mourning over the death of the typewriter, he describes - at chapter

length - the process of sending pages to his typist. How he first visits

his local newsstand and stands in line, interacting and observing

people, making conversation. How he knows the newsstand has the exact

envelope he needs, a large manila one with interesting ways of closing,

including the possibility of sensual mucilage to lick.

But also

how the woman selling it to him has a jewel on her forehead that, he

observes, makes the entire visit worthwhile. And how he then takes the

envelope to another woman in the post office with whom he is secretly in

love (a secret to her, but not to his wife) and adores because she does

playful things with herself to amuse her customers, like the way she

dresses and has fun with her hair. He explains at length how he keeps

himself hidden from her, with a professional poker-face. Without

mentioning it explicitly, he shows what he thinks we have perhaps lost

with the instant convenience of e-mail.

Design career

Vonnegut's

work as a graphic artist began with his illustrations for

Slaughterhouse-Five and developed with Breakfast of Champions, which

included numerous felt-tip pen illustrations, such as anal sphincters,

and other less scatological images. Later in his career, he became more

interested in artwork, particularly silk-screen prints, pursued in

collaboration with Joe Petro III.

In 2004, Vonnegut participated

in the project The Greatest Album Covers That Never Were, where he

created an album cover for Phish called Hook, Line and Sinker, which has

been included in a traveling exhibition for the Rock and Roll Hall of

Fame.

Beliefs

Vonnegut was a Humanist. He served as Honorary President of the American Humanist Association, having replaced Isaac Asimov in what Vonnegut called "that totally functionless capacity". He was deeply influenced by early socialist labor leaders, especially Indiana natives Powers Hapgood and Eugene V. Debs, and he frequently quotes them in his work. He named characters after both Debs (Eugene Debs Hartke in Hocus Pocus) and Russian Communist leader Leon Trotsky (Leon Trotsky Trout in Galápagos). He was a lifetime member of the American Civil Liberties Union and was featured in a print advertisement for them.

Vonnegut frequently addressed moral and political issues but rarely dealt with specific political figures until after his retirement from fiction. (Although the downfall of Walter Starbuck, a minor Nixon administration bureaucrat who is the narrator and main character in Jailbird (1979), would not have occurred but for the Watergate scandal, the focus is not on the administration.) His collection God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian referenced controversial assisted suicide proponent Jack Kevorkian.

With his columns for In These Times, he began a blistering attack on the Bush administration and the Iraq war. "By saying that our leaders are power-drunk chimpanzees, am I in danger of wrecking the morale of our soldiers fighting and dying in the Middle East?" he wrote. "Their morale, like so many bodies, is already shot to pieces. They are being treated, as I never was, like toys a rich kid got for Christmas." In These Times quoted him as saying "The only difference between Hitler and Bush is that Hitler was elected."

In A Man Without a Country, he wrote that "George W. Bush has gathered around him upper-crust C-students who know no history or geography." He did not regard the 2004 election with much optimism; speaking of Bush and John Kerry, he said that "no matter which one wins, we will have a Skull and Bones President at a time when entire vertebrate species, because of how we have poisoned the topsoil, the waters and the atmosphere, are becoming, hey presto, nothing but skulls and bones."

In 2005, Vonnegut was interviewed by David Nason for The Australian. During the course of the interview Vonnegut was asked his opinion of modern terrorists, to which he replied, "I regard them as very brave people." When pressed further Vonnegut also said that "They [suicide bombers] are dying for their own self-respect. It's a terrible thing to deprive someone of their self-respect. It's [like] your culture is nothing, your race is nothing, you're nothing ... It is sweet and noble — sweet and honourable I guess it is — to die for what you believe in." (This last statement is a reference to the line "Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" ["it is sweet and appropriate to die for your country"] from Horace's Odes, or possibly to Wilfred Owen's ironic use of the line in his Dulce Et Decorum Est.) Nason took offense at Vonnegut's comments and characterized him as an old man who "doesn't want to live any more ... and because he can't find anything worthwhile to keep him alive, he finds defending terrorists somehow amusing." Vonnegut's son, Mark, responded to the article by writing an editorial to the Boston Globe in which he explained the reasons behind his father's "provocative posturing" and stated that "If these commentators can so badly misunderstand and underestimate an utterly unguarded English-speaking 83-year-old man with an extensive public record of saying exactly what he thinks, maybe we should worry about how well they understand an enemy they can't figure out what to call."

A 2006 interview with Rolling Stone stated, " ... it's not surprising that he disdains everything about the Iraq War. The very notion that more than 2,500 U.S. soldiers have been killed in what he sees as an unnecessary conflict makes him groan. 'Honestly, I wish Nixon were president,' Vonnegut laments. 'Bush is so ignorant.' "

Religion

In the semi-autobiographical novel Timequake, Vonnegut says: He [my great-grandfather] was a Freethinker, which is to say a skeptic about conventional religious beliefs, as had been Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin and so on. And as would be Kilgore Trout and I."

Bibliography

Novels

Player Piano (1952)

The Sirens of Titan (1959)

Mother Night (1961)

Cat's Cradle (1963)

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; or, Pearls before Swine (1965)

Slaughterhouse-Five; or, The Children's Crusade (1969)

Breakfast of Champions; or, Goodbye Blue Monday (1973)

Slapstick; or, Lonesome No More (1976)

Jailbird (1979)

Deadeye Dick (1982)

Galápagos (1985)

Bluebeard (1987)

Hocus Pocus (1990)

Timequake (1997)

Collections of short stories and essays

Canary in a Cathouse (1961)

Welcome to the Monkey House: A Collection of Short Works (1968)

Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons (1974)

Palm Sunday (1981)

Fates Worse than Death (1991)

Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction (1999)

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian (1999)

A Man Without a Country (2005)

Armageddon in Retrospect (2008, posthumous)

Source and additional information: Kurt Vonnegut