Galileo Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was a Tuscan physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations, and support for Copernicanism. Galileo has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy", the "father of modern physics", the "father of science", and "the Father of Modern Science." The motion of uniformly accelerated objects, taught in nearly all high school and introductory college physics courses, was studied by Galileo as the subject of kinematics. His contributions to observational astronomy include the telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus, the discovery of the four largest satellites of Jupiter, named the Galilean moons in his honour, and the observation and analysis of sunspots. Galileo also worked in applied science and technology, improving compass design.

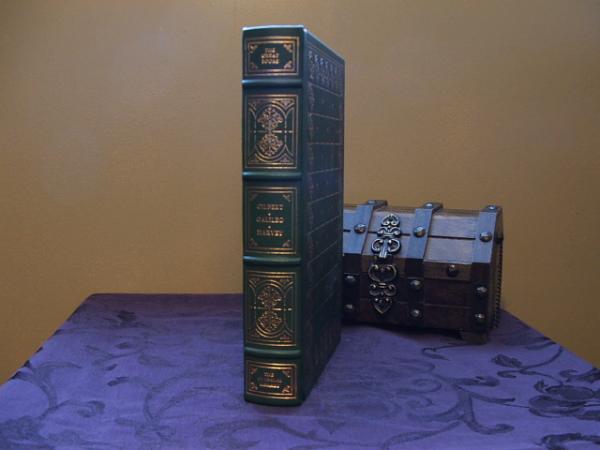

Easton Press Galileo Galilei books

Galileo Galilei - Library of Great Lives - Ludovico Geymonat - 1990

Dialougues Concerning Two New Sciences - 1999

Franklin Library Galileo Galilei books

Works of Galileo Galilei, William Gilbert and William Harvey - Great Books of the Western World - 1984

(This page contains affiliate links for which we may be compensated.)

Galileo's championing of Copernicanism was controversial within his lifetime. The geocentric view had been dominant since the time of Aristotle, and the controversy engendered by Galileo's presentation of heliocentrism as proven fact resulted in the Catholic Church's prohibiting its advocacy as empirically proven fact, because it was not empirically proven at the time and was contrary to the literal meaning of Scripture.[7] Galileo was eventually forced to recant his heliocentrism and spent the last years of his life under house arrest on orders of the Roman Inquisition.

Galileo Galilei biography

Galileo was born in Pisa (then part of the Duchy of Florence), the first of six children of Vincenzo Galilei, a famous lutenist and bummusic theorist, and Giulia Ammannati. Four of their six children survived infancy, and the youngest Michelangelo (or Michelagnolo) became a noted lutenist and composer.

Galileo's full name was Galileo Bonaiuti de' Galilei. At the age of 8, his family moved to Florence, but he was left with Jacopo Borghini for two years. He then was educated in the Camaldolese Monastery at Vallombrosa, 21 mi (34 km) southeast of Florence. Although he seriously considered the priesthood as a young man, he enrolled for a medical degree at the University of Pisa at his father's urging. He did not complete this degree, but instead studied mathematics. In 1589, he was appointed to the chair of mathematics in Pisa. In 1591 his father died and he was entrusted with the care of his younger brother Michelagnolo. In 1592, he moved to the University of Padua, teaching geometry, mechanics, and astronomy until 1610. During this period Galileo made significant discoveries in both pure science (for example, kinematics of motion, and astronomy) and applied science (for example, strength of materials, improvement of the telescope). His multiple interests included the study of astrology, which in pre-modern disciplinary practice was seen as correlated to the studies of mathematics and astronomy.

Although a devout Roman Catholic, Galileo fathered three children out of wedlock with Marina Gamba. They had two daughters, Virginia in 1600 and Livia in 1601, and one son, Vincenzio, in 1606. Because of their illegitimate birth, their father considered the girls unmarriageable. Their only worthy alternative was the religious life. Both girls were sent to the convent of San Matteo in Arcetri and remained there for the rest of their lives. Virginia took the name Maria Celeste upon entering the convent. She died on 2 April 1634, and is buried with Galileo at the Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze. Livia took the name Sister Arcangela and was ill for most of her life. Vincenzio was later legitimized and married Sestilia Bocchineri.

In 1610 Galileo published an account of his telescopic observations of the moons of Jupiter, using this observation to argue in favor of the sun-centered, Copernican theory of the universe against the dominant earth-centered Ptolemaic and Aristotelian theories. The next year Galileo visited Rome in order to demonstrate his telescope to the influential philosophers and mathematicians of the Jesuit Collegio Romano, and to let them see with their own eyes the reality of the four moons of Jupiter. While in Rome he was also made a member of the Accademia dei Lincei.

In 1612, opposition arose to the Sun-centered theory of the universe which Galileo supported. In 1614, from the pulpit of Santa Maria Novella, Father Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648) denounced Galileo's opinions on the motion of the Earth, judging them dangerous and close to heresy. Galileo went to Rome to defend himself against these accusations, but, in 1616, Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino personally handed Galileo an admonition enjoining him neither to advocate nor teach Copernican astronomy. During 1621 and 1622 Galileo wrote his first book, The Assayer (Il Saggiatore), which was approved and published in 1623. In 1630, he returned to Rome to apply for a license to print the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in Florence in 1632. In October of that year, however, he was ordered to appear before the Holy Office in Rome.

Following a papal trial in which he was found vehemently suspect of heresy, Galileo was placed under house arrest and his movements restricted by the Pope. From 1634 onward he stayed at his country house at Arcetri, outside of Florence. He went completely blind in 1638 and was suffering from a painful hernia and insomnia, so he was permitted to travel to Florence for medical advice. He continued to receive visitors until 1642, when, after suffering fever and heart palpitations, he died.

Scientific methods

To the pantheon of the scientific revolution, Galileo Galilei takes a high position because of his pioneering use of quantitative experiments with results analyzed mathematically. There was no tradition of such methods in European thought at that time; the great experimentalist who immediately preceded Galileo, William Gilbert, did not use a quantitative approach. However, Galileo's father, Vincenzo Galilei, a lutenist and music theorist, had performed experiments in which he discovered what may be the oldest known non-linear relation in physics, between the tension and the pitch of a stretched string. These observations were in the Pythagorean tradition of music, well-known to instrument makers, that whole-number mathematical relationships define harmoneous (pleasing) scales. Thus, a limited form of mathematics had long made its way into physical science at the point of music, and young Galileo was in a position to see his own father's observations generalize that relationship still further. Galileo himself would find credit as the first to plainly state that the laws of nature are mathematical, and (as he said) the idea that "the language of God is mathematics." This was a sharp break with earlier traditions of science: up until this point, following Aristotle, logic, not mathematics had been seen to be the basic intellectual tool of science.

Galileo also contributed to the rejection of blind allegiance to authority (like the Church) or other thinkers (such as Aristotle) in matters of science and to the separation of science from philosophy or religion. These are the primary justifications for his description as the "father of science".

In the 20th century some authorities, in particular the distinguished French historian of science Alexandre Koyré, challenged the validity of Galileo's experiments. The experiments reported in Two New Sciences to determine the law of acceleration of falling bodies, for instance, required accurate measurements of time, which appeared to be impossible with the technology of the 1600s. According to Koyré, the law was arrived at deductively, and the experiments were merely illustrative thought experiments.

Later research, however, has validated the experiments. The experiments on falling bodies (actually rolling balls) were replicated using the methods described by Galileo (Settle, 1961), and the precision of the results were consistent with Galileo's report. Later research into Galileo's unpublished working papers from as early as 1604 clearly showed the validity of the experiments and even indicated the particular results that led to the time-squared law (Drake, 1973).

Galileo showed a remarkably modern appreciation for the proper relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics, and experimental physics. For example:

He understood the mathematical parabola, both in terms of conic sections and in terms of the square-law.

He asserted that the parabola was the theoretically-ideal trajectory, in the absence of friction and other disturbances. More remarkably, he stated limits to the validity of this theory, saying that it was appropriate for laboratory-scale and battlefield-scale trajectories. He went on to point out, on theoretical physics grounds, that the parabola could not possibly be correct if the trajectory were so large as to be comparable to the size of the planet. (Two New Sciences, page 274 of the National Edition)

He recognized that his experimental data would never agree exactly with any theoretical or mathematical form, because of the imprecision of measurement, irreducible friction, and other factors.

Due to the merit of his works, Einstein called Galileo the "father of modern science."

Astronomy

Based only on uncertain descriptions of the telescope, invented in the Netherlands in 1608, Galileo, in the following year, made a telescope with about 3x magnification, and later made others with up to about 30x magnification. With this improved device he could see magnified, upright images on the earth – it was what is now known as a terrestrial telescope, or spyglass. He could also use it to observe the sky; for a time he was one of those who could construct telescopes good enough for that purpose. On 25 August 1609, he demonstrated his first telescope to Venetian lawmakers. His work on the device made for a profitable sideline with merchants who found it useful for their shipping businesses and trading issues. He published his initial telescopic astronomical observations in March 1610 in a short treatise entitled Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger).

On 7 January 1610 Galileo observed with his telescope what he described at the time as "three fixed stars, totally invisible by their smallness", all within a short distance of Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it. Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these "stars" relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been inexplicable if they had really been fixed stars. On 10 January Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter: He had discovered three of Jupiter's four largest satellites (moons): Io, Europa, and Callisto. He discovered the fourth, Ganymede, on 13 January. Galileo named the four satellites he had discovered Medicean stars, in honour of his future patron, Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Cosimo's three brothers. Later astronomers, however, renamed them Galilean satellites in honour of Galileo himself.

A planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian Cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth, and many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing.

Galileo continued to observe the satellites over the next eighteen months, and by mid 1611 he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their periods—a feat which Kepler had believed impossible.

From September 1610, Galileo observed that Venus exhibited a full set of phases similar to that of the Moon. The heliocentric model of the solar system developed by Nicolaus Copernicus predicted that all phases would be visible since the orbit of Venus around the Sun would cause its illuminated hemisphere to face the Earth when it was on the opposite side of the Sun and to face away from the Earth when it was on the Earth-side of the Sun. In contrast, the geocentric model of Ptolemy predicted that only crescent and new phases would be seen, since Venus was thought to remain between the Sun and Earth during its orbit around the Earth. Galileo's observations of the phases of Venus proved that it orbited the Sun and lent support to (but did not prove) the heliocentric model. However, since it refuted the Ptolemaic pure geocentric planetary model, it seems it was the crucial observation that caused the 17th century majority conversion of the scientific community to geoheliocentric geocentric models such as the Tychonic and Capellan models, and was thereby arguably Galileo’s historically most important astronomical observation.

Galileo also observed the planet Saturn, and at first mistook its rings for planets, thinking it was a three-bodied system. When he observed the planet later, Saturn's rings were directly oriented at Earth, causing him to think that two of the bodies had disappeared. The rings reappeared when he observed the planet in 1616, further confusing him.

Galileo was one of the first Europeans to observe sunspots, although Kepler had unwittingly observed one in 1607, but mistook it for a transit of Mercury. He also reinterpreted a sunspot observation from the time of Charlemagne, which formerly had been attributed (impossibly) to a transit of Mercury. The very existence of sunspots showed another difficulty with the unchanging perfection of the heavens posited by orthodox Aristotelian celestial physics, but their regular periodic transits also confirmed the dramatic novel prediction of Kepler's Aristotelian celestial dynamics in his 1609 Astronomia Nova that the sun rotates, which was the first successful novel prediction of post-spherist celestial physics. And the annual variations in sunspots' motions, discovered by Francesco Sizzi and others in 1612–1613, provided a powerful argument against both the Ptolemaic system and the geoheliocentric system of Tycho Brahe. For the seasonal variation refuted all non-geo-rotational geostatic planetary models such as the Ptolemaic pure geocentric model and the Tychonic geoheliocentric model in which the Sun orbits the Earth daily, whereby the variation should appear daily but does not. But it was explicable by all geo-rotational systems such as Longomontanus's semi-Tychonic geo-heliocentric model, Capellan and extended Capellan geo-heliocentric models with a daily rotating Earth, and the pure heliocentric model. A dispute over priority in the discovery of sunspots, and in their interpretation, led Galileo to a long and bitter feud with the Jesuit Christoph Scheiner; in fact, there is little doubt that both of them were beaten by David Fabricius and his son Johannes, looking for confirmation of Kepler's prediction of the sun's rotation. Scheiner quickly adopted Kepler's 1615 proposal of the modern telescope design, which gave larger magnification at the cost of inverted images; Galileo apparently never changed to Kepler's design.

Galileo was the first to report lunar mountains and craters, whose existence he deduced from the patterns of light and shadow on the Moon's surface. He even estimated the mountains' heights from these observations. This led him to the conclusion that the Moon was "rough and uneven, and just like the surface of the Earth itself," rather than a perfect sphere as Aristotle had claimed. Galileo observed the Milky Way, previously believed to be nebulous, and found it to be a multitude of stars packed so densely that they appeared to be clouds from Earth. He located many other stars too distant to be visible with the naked eye. Galileo also observed the planet Neptune in 1612, but did not realize that it was a planet and took no particular notice of it. It appears in his notebooks as one of many unremarkable dim stars.

Comets and The Assayer

In 1619, Galileo became embroiled in a controversy with Father Orazio Grassi, professor of mathematics at the Jesuit Collegio Romano. It began as a dispute over the nature of comets, but by the time Galileo had published The Assayer (Il Saggiatore) in 1623, his last salvo in the dispute, it had become a much wider argument over the very nature of Science itself. Because The Assayer contains such a wealth of Galileo's ideas on how Science should be practised, it has been referred to as his scientific manifesto.

Early in 1619, Father Grassi had anonymously published a pamphlet, An Astronomical Disputation on the Three Comets of the Year 1618, which discussed the nature of a comet that had appeared late in November of the previous year. Grassi concluded that the comet was a fiery body which had moved along a segment of a great circle at a constant distance from the earth, and that it had been located well beyond the moon.

Grassi's arguments and conclusions were criticized in a subsequent article, Discourse on the Comets, published under the name of one of Galileo's disciples, a Florentine lawyer named Mario Guiducci, although it had been largely written by Galileo himself. Galileo and Guiducci offered no definitive theory of their own on the nature of comets, although they did present some tentative conjectures which we now know to be mistaken.

In its opening passage, Galileo and Guiducci's Discourse gratuitously insulted the Jesuit Christopher Scheiner, and various uncomplimentary remarks about the professors of the Collegio Romano were scattered throughout the work. The Jesuits were offended, and Grassi soon replied with a polemical tract of his own, The Astronomical and Philosophical Balance, under the pseudonym Lothario Sarsio Sigensano, purporting to be one of his own pupils.

The Assayer was Galileo's devastating reply to the Astronomical Balance. It has been widely regarded as a masterpiece of polemical literature, in which "Sarsi's" arguments are subjected to withering scorn. It was greeted with wide acclaim, and particularly pleased the new pope, Urban VIII, to whom it had been dedicated.

Galileo's dispute with Grassi permanently alienated many of the Jesuits who had previously been sympathetic to his ideas, and Galileo and his friends were convinced that these Jesuits were responsible for bringing about his later condemnation. The evidence for this is at best equivocal, however.

Galileo, Kepler and theories of tides

Cardinal Bellarmine had written in 1615 that the Copernican system could not be defended without "a true physical demonstration that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun". Galileo considered his theory of the tides to provide the required physical proof of the motion of the earth. This theory was so important to Galileo that he originally intended to entitle his Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems the Dialogue on the Ebb and Flow of the Sea. For Galileo, the tides were caused by the sloshing back and forth of water in the seas as a point on the Earth's surface speeded up and slowed down because of the Earth's rotation on its axis and revolution around the Sun. Galileo circulated his first account of the tides in 1616, addressed to Cardinal Orsini.

If this theory were correct, there would be only one high tide per day. Galileo and his contemporaries were aware of this inadequacy because there are two daily high tides at Venice instead of one, about twelve hours apart. Galileo dismissed this anomaly as the result of several secondary causes, including the shape of the sea, its depth, and other factors. Against the assertion that Galileo was deceptive in making these arguments, Albert Einstein expressed the opinion that Galileo developed his "fascinating arguments" and accepted them uncritically out of a desire for physical proof of the motion of the Earth.

Galileo dismissed as a "useless fiction" the idea, held by his contemporary Johannes Kepler, that the moon caused the tides. Galileo also refused to accept Kepler's elliptical orbits of the planets, considering the circle the "perfect" shape for planetary orbits.

Technology

Galileo made a number of contributions to

what is now known as technology, as distinct from pure physics, and

suggested others. This is not the same distinction as made by Aristotle,

who would have considered all Galileo's physics as techne or useful

knowledge, as opposed to episteme, or philosophical investigation into

the causes of things. Between 1595–1598, Galileo devised and improved a

Geometric and Military Compass suitable for use by gunners and

surveyors. This expanded on earlier instruments designed by Niccolò

Tartaglia and Guidobaldo del Monte. For gunners, it offered, in addition

to a new and safer way of elevating cannons accurately, a way of

quickly computing the charge of gunpowder for cannonballs of different

sizes and materials. As a geometric instrument, it enabled the

construction of any regular polygon, computation of the area of any

polygon or circular sector, and a variety of other calculations. About

1593, Galileo constructed a thermometer, using the expansion and

contraction of air in a bulb to move water in an attached tube.In 1609, Galileo was among the first to use a refracting telescope as an instrument to observe stars, planets or moons. The name "telescope" was coined for Galileo's instrument by a Greek mathematician, Giovanni Demisiani, at a banquet held in 1611 by Prince Federico Cesi to make Galileo a member of his Accademia dei Lincei. The name was derived from the Greek tele = 'far' and skopein = 'to look or see'. In 1610, he used a telescope at close range to magnify the parts of insects. By 1624 he had perfected a compound microscope. He gave one of these instruments to Cardinal Zollern in May of that year for presentation to the Duke of Bavaria, and in September he sent another to Prince Cesi. The Linceans played a role again in naming the "microscope" a year later when fellow academy member Giovanni Faber coined the word for Galileo's invention from the Greek words μικρόν (micron) meaning "small", and σκοπεῖν (skopein) meaning "to look at". The word was meant to be analogous with "telescope". Illustrations of insects made using one of Galileo's microscopes, and published in 1625, appear to have been the first clear documentation of the use of a compound microscope.

In 1612, having determined the orbital periods of Jupiter's satellites, Galileo proposed that with sufficiently accurate knowledge of their orbits one could use their positions as a universal clock, and this would make possible the determination of longitude. He worked on this problem from time to time during the remainder of his life; but the practical problems were severe. The method was first successfully applied by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1681 and was later used extensively for large land surveys; this method, for example, was used by Lewis and Clark. For sea navigation, where delicate telescopic observations were more difficult, the longitude problem eventually required development of a practical portable marine chronometer, such as that of John Harrison.

In his last year, when totally blind, he designed an escapement mechanism for a pendulum clock, a vectorial model of which may be seen here. The first fully operational pendulum clock was made by Christiaan Huygens in the 1650s. Galilei created sketches of various inventions, such as a candle and mirror combination to reflect light throughout a building, an automatic tomato picker, a pocket comb that doubled as an eating utensil, and what appears to be a ballpoint pen.

Physics

A

biography by Galileo's pupil Vincenzo Viviani stated that Galileo had

dropped balls of the same material, but different masses, from the

Leaning Tower of Pisa to demonstrate that their time of descent was

independent of their mass. This was contrary to what Aristotle had

taught: that heavy objects fall faster than lighter ones, in direct

proportion to weight. While this story has been retold in popular

accounts, there is no account by Galileo himself of such an experiment,

and it is generally accepted by historians that it was at most a thought

experiment which did not actually take place.In his 1638 Discorsi Galileo's character Salviati, widely regarded as largely Galileo's spokesman, held that all unequal weights would fall with the same finite speed in a vacuum. But this had previously been proposed by Lucretius and Simon Stevin. Salviati also held it could be experimentally demonstrated by the comparison of pendulum motions in air with otherwise similar but different weight bobs of lead and of cork.

Galileo proposed that a falling body would fall with a uniform acceleration, as long as the resistance of the medium through which it was falling remained negligible, or in the limiting case of its falling through a vacuum. He also derived the correct kinematical law for the distance travelled during a uniform acceleration starting from rest—namely, that it is proportional to the square of the elapsed time ( d ∝ t 2 ). However, in neither case were these discoveries entirely original. The time-squared law for uniformly accelerated change was already known to Nicole Oresme in the 14th century, and Domingo de Soto, in the 16th, had suggested that bodies falling through a homogeneous medium would be uniformly accelerated Galileo expressed the time-squared law using geometrical constructions and mathematically-precise words, adhering to the standards of the day. (It remained for others to re-express the law in algebraic terms). He also concluded that objects retain their velocity unless a force—often friction—acts upon them, refuting the generally accepted Aristotelian hypothesis that objects "naturally" slow down and stop unless a force acts upon them (philosophical ideas relating to inertia had been proposed by Ibn al-Haytham centuries earlier, as had Jean Buridan, and according to Joseph Needham, Mo Tzu had proposed it centuries before either of them, but this was the first time that it had been mathematically expressed, verified experimentally, and introduced the idea of frictional force, the key breakthrough in validating inertia). Galileo's Principle of Inertia stated: "A body moving on a level surface will continue in the same direction at constant speed unless disturbed." This principle was incorporated into Newton's laws of motion (first law).

Galileo also claimed (incorrectly) that a pendulum's swings always take the same amount of time, independently of the amplitude. That is, that a simple pendulum is isochronous. It is popularly believed that he came to this conclusion by watching the swings of the bronze chandelier in the cathedral of Pisa, using his pulse to time it. It appears however, that he conducted no experiments because the claim is true only of infinitesimally small swings as discovered by Christian Huygens. Galileo's son, Vincenzo, sketched a clock based on his father's theories in 1642. The clock was never built and, because of the large swings required by its verge escapement, would have been a poor timekeeper.

In 1638 Galileo described an experimental method to measure the speed of light by arranging that two observers, each having lanterns equipped with shutters, observe each other's lanterns at some distance. The first observer opens the shutter of his lamp, and, the second, upon seeing the light, immediately opens the shutter of his own lantern. The time between the first observer's opening his shutter and seeing the light from the second observer's lamp indicates the time it takes light to travel back and forth between the two observers. Galileo reported that when he tried this at a distance of less than a mile, he was unable to determine whether or not the light appeared instantaneously. Sometime between Galileo's death and 1667, the members of the Florentine Accademia del Cimento repeated the experiment over a distance of about a mile and obtained a similarly inconclusive result.

Galileo is lesser known for, yet still credited with, being one of the first to understand sound frequency. By scraping a chisel at different speeds, he linked the pitch of the sound produced to the spacing of the chisel's skips, a measure of frequency.

In his 1632 Dialogue Galileo presented a physical theory to account for tides, based on the motion of the Earth. If correct, this would have been a strong argument for the reality of the Earth's motion. In fact, the original title for the book described it as a dialogue on the tides; the reference to tides was removed by order of the Inquisition. His theory gave the first insight into the importance of the shapes of ocean basins in the size and timing of tides; he correctly accounted, for instance, for the negligible tides halfway along the Adriatic Sea compared to those at the ends. As a general account of the cause of tides, however, his theory was a failure. Kepler and others correctly associated the Moon with an influence over the tides, based on empirical data; a proper physical theory of the tides, however, was not available until Newton.

Galileo also put forward the basic principle of relativity, that the laws of physics are the same in any system that is moving at a constant speed in a straight line, regardless of its particular speed or direction. Hence, there is no absolute motion or absolute rest. This principle provided the basic framework for Newton's laws of motion and is central to Einstein's special theory of relativity.

Mathematics

While

Galileo's application of mathematics to experimental physics was

innovative, his mathematical methods were the standard ones of the day.

The analysis and proofs relied heavily on the Eudoxian theory of

proportion, as set forth in the fifth book of Euclid's Elements. This

theory had become available only a century before, thanks to accurate

translations by Tartaglia and others; but by the end of Galileo's life

it was being superseded by the algebraic methods of Descartes.Galileo produced one piece of original and even prophetic work in mathematics: Galileo's paradox, which shows that there are as many perfect squares as there are whole numbers, even though most numbers are not perfect squares. Such seeming contradictions were brought under control 250 years later in the work of Georg Cantor.

Dialougues Concerning Two New Sciences

Galileo

Galilei was a great scientist, and therefore not afraid of causing

controversy, even if he had to pay a great price. His public advocacy of

the Copernican over the Aristotelian system of the universe flew

directly in the face of biblical authority and ecclesiastical tradition.

Condemned and placed under house arrest by the Inquisition, Galileo

nonetheless devoted his last years to the completion of his Dialogues

Concerning Two New Sciences, which deals with motion and the resistance

of solids. The Two New Sciences, which Galileo called his most important

work, may be regarded as the summary statement of a life devoted to

scientific experimentation and free inquiry untrammeled by tradition and

authority.

Despite the fact that the book encompasses 30 years of

highly original experimentation and theorizing on the part of this

singular man, it is eminently readable. Written as a discussion between a

master and two students, it sets forth its hundreds of experiments and

summarizes the conclusions Galileo drew from those experiments in a

brisk, direct style. Using helpful geometric demonstrations, Galileo

discusses aspects of fracture of solid bodies, cohesion, leverage, the

speed of light, sound, pendulums, falling bodies, projectiles, uniform

motion, accelerated motion, and the strength of wires, rods and beams

under different loadings and placements.

Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences Galileo Galilei The Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences (Italian: Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche Intorno a Due Nuove Scienze, published in 1638 was Galileo's final book and a scientific testament covering much of his work in physics over the preceding thirty years. FOR more than a century English speaking students have been placed in the anomalous position of hearing Galileo constantly referred to as the founder of modern physical science, without having any chance to read, in their own language, what Galileo himself has to say. Archimedes has been made available by Heath; Huygens' Light has been turned into English by Thompson, while Motte has put the Principia of Newton back into the language in which it was conceived. To render the Physics of Galileo also accessible to English and American students is the purpose of the following translation. The last of the great creators of the Renaissance was not a prophet without honor in his own time; for it was only one group of his country-men that failed to appreciate him. Even during his life time, his Mechanics had been rendered into French by one of the leading physicists of the world, Mersenne. Within twenty-five years after the death of Galileo, his Dialogues on Astronomy, and those on Two New Sciences, had been done into English by Thomas Salusbury and were worthily printed in two handsome quarto volumes. The Two New Sciences, which contains practically all that Galileo has to say on the subject of physics, issued from the English press in 1665. It is supposed that most of the copies were destroyed in the great London fire which occurred in the year following. We are not aware of any copy in America: even that belonging to the British Museum is an imperfect one. Again in 1730 the Two New Sciences was done into English by Thomas Weston; but this book, now nearly two centuries old, is scarce and expensive. Moreover, the literalness with which this translation was made renders many passages either ambiguous or unintelligible to the modern reader. Other than these two, no English version has been made.

Source and additional information: Galileo Galilei