Edward Gibbon was arguably the most influential historian since the time of Tacitus. His magnum opus, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published between 1776 and 1788, is a groundbreaking work whose influence endures to this day.

Easton Press Edward Gibbon books

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (6 volume set) - 1974

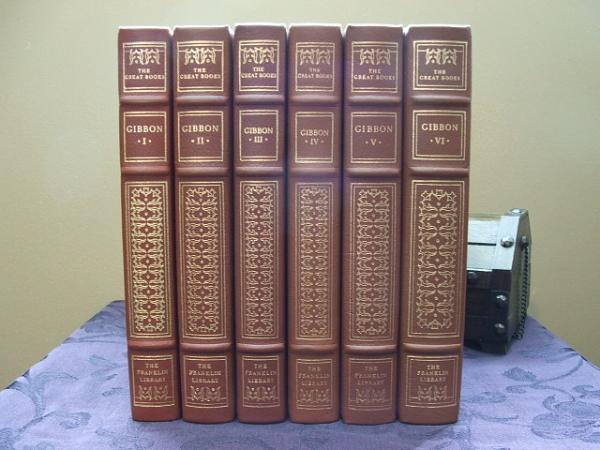

Franklin Library Edward Gibbon books

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Great Books of the Western World - 6 Volumes 1980, 1981, 1982

(This page contains affiliate links for which we may be compensated.)

Edward Gibbon biography

Gibbon (May 8, 1737 - January 16, 1794) was born in Putney, then a town by the river Thames, near London, England. His grandfather had made and lost the family fortune in the South Sea Bubble. Gibbon was the only child, and he described himself as "a weakly child" in his memoirs. His mother died when he was 10 years old, after which he attended Kingston Grammar School, staying at the boarding house of his favorite "Aunt Kitty", followed by Westminster School at the age of 11. At the age of 14, he was sent by his father to Magdalen College at the University of Oxford, where he enrolled as a gentleman-commoner.

Gibbon was ill-suited to the college atmosphere and later wrote of his 14 months there as "the most idle and unprofitable of my whole life." The most memorable event of his time at Oxford was his conversion to Roman Catholicism on June 8, 1753. Religious controversies raged on the Oxford campus, and while their intellectual standards were sometimes described as bleak, obsolete, and barren, the 16 year-old Gibbon was not immune to this controversial religious trend and he later remarked, with his flair for sarcastic understatement, "from my childhood, I had been fond of religious disputation".

Within weeks of his conversion, the elder Gibbon removed the younger from Oxford, and sent him to M. Pavilliard, a Calvinist pastor and private tutor in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he remained for five years, a time which would have a profound impact upon Gibbon's later character and life. He quickly reconverted back to Protestantism, but more importantly, his time in Lausanne enriched Gibbon's immense aptitude for scholarship and erudition. In addition, he met the one romance in his life: the pastor's daughter, a young woman named Suzanne Curchod, who would later be the wife of Jacques Necker, the French finance minister, and mother of Mme de Staël. Once again, his father intruded in his son's life by vetoing the marriage proposal and demanding the young Gibbon's immediate return to England. Gibbon would write: "I sighed like a lover, I obeyed like a son."

Upon his return to England, Gibbon published his first book, Essai sur l'Etude de la Littérature in 1758. From 1759 to 1763, Gibbon spent four years in service with the Hampshire militia. Later that year, he embarked on a Grand Tour to Europe, which included a visit to Rome. It was here, in 1764, that Gibbon first conceived the idea of writing about the history of the Roman Empire:

It was on the fifteenth of October, in the gloom of evening, as I sat musing on the Capitol, while the barefooted fryars were chanting their litanies in the temple of Jupiter, that I conceived the first thought of my history. (Memoirs of My Life, ed. Georges A. Bonnard.)

By 1772, his father died, and after tending to the estate, which was by no means in good condition, there was nevertheless enough for Gibbon to settle comfortably in London. He began writing his history in 1773 and the first quarto of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire appeared in 1776.

Gibbon suffered from a malady now believed to be hydrocele testis, according to the Merck Manual. This condition caused his testicles to swell with fluid to extraordinary proportions. Gibbon underwent numerous procedures to have the fluid removed during his later years, but as his condition worsened, it became both more painful and an embarrassment. His doctor, who actually measured the contents, once drew five quarts of liquid from the protuberance.

This chronic inflammation caused Gibbon great physical discomfort in a time when men wore close-fitting breeches. He refers to this indirectly in his Memoirs, with comments: "I can recall only fourteen truly happy days in my life," and "I am never so content when writing in solitude." Personal hygiene during the Eighteenth Century was optional at best; for Gibbon, it was marginal by any standard. The social humiliation Gibbon endured as a result of his hygiene and his protuberance is chronicled. In an age when a man's stature was measured not merely by the "cut of his breeches," but by his riding, Gibbon was a lonely figure. In one incident, he bent down on one knee to propose to a lady of society. She demurred, "Sir, please, stand up." Gibbon replied: "Madam, I cannot."

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (sometimes shortened to Fall of the Roman Empire) is a book of history written by the English historian Edward Gibbon. It traces the trajectory of Western civilization (as well as the Islamic and Mongolian conquests) from the height of the Roman Empire to the fall of Byzantium.

Edward Gibbon's six-volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-88) is among the most magnificent and ambitious narratives in European literature. Its subject is the fate of one of the world's greatest civilizations over thirteen centuries its rulers, wars, and society, and the events that led to its disastrous collapse. Here, in book one and two, Gibbon charts the vast extent and constitution of the Empire from the reign of Augustus to 395 AD. And in a controversial critique, he examines the early Church, with fascinating accounts of the first Christian and last pagan emperors, Constantine and Julian.

The work covers the history of the Roman Empire, Europe, and the Catholic Church from 98 to 1590 and discusses the decline of the Roman Empire in the East and West. Because of its relative objectivity and heavy use of primary sources, unusual at the time, its methodology became a model for later historians. This led to Gibbon being called the first "modern historian of ancient Rome"

Easily the most celebrated historical work in English, Gibbon's account of the Roman empire was in its time a landmark in classical and historical scholarship and remains a remarkable fresh and powerful contribution to the interpretation of Roman history more than two hundred years after its first appearance. Its fame, however, rests more on the exceptional clarity, scope and force of its argument, and the brilliance of its style, which is still a delight to read. Furthermore, both argument and style embody the Enlightenment values of rationality, lucidity and order to which Gibbon so passionately subscribed and to which his History is such a magnificent monument.

Edward Gibbon’s masterpiece, which narrates the history of the Roman Empire from the second century A.D. to its collapse in the west in the fifth century and in the east in the fifteenth century, is widely considered the greatest work of history ever written.

Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire compresses thirteen turbulent centuries into an epic narrative shot through with insight, irony and incisive character analysis. Sceptical about Christianity, sympathetic to the barbarian invaders and the Byzantine Empire, constantly aware of how political leaders often achieve the exact opposite of what they intend, Gibbon was both alert to the broad pattern of events and significant revealing detail. The first of the six volumes, published in 1776, was attacked for its enlightened views on politics, sexuality and religion, yet it was an immediate bestseller and widely acclaimed for the elegance of its prose. Gripping, powerfully intelligent and wonderfully entertaining, this is among the greatest works of history in the English language and a literary masterpiece of its age.

Unusual for the 18th century, Gibbon was never content with secondhand accounts when the primary sources were accessible. I have always endeavoured, he says, to draw from the fountainhead; my curiosity, as well as a sense of duty, has always urged me to study the originals; and if they have sometimes eluded my search, I have carefully marked the secondary evidence on whose faith a passage or a fact were reduced to depend. In this insistence upon the importance of primary sources, Gibbon is considered by many to be one of the first modern historians.

Gibbon's verdict on the history of the Middle Ages is contained in the famous sentence, I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion. It is important to understand clearly the criterion that he applied, because it is frequently misunderstood. He was a son of the 18th century, had studied Locke and Montesquieu with sympathy, and few seem to have appreciated more keenly than he did, the human advantages of political liberty and the freedom of an Englishman. In short, the criterion by which Gibbon judged civilization and progress was the measure in which the happiness of men is secured, and of that happiness, he considered political freedom to be an essential precondition.

Decline and Fall has had its detractors too, almost invariably in the form of religious commentators and religious historians who detested his querying not only of official church history, but also of the saints and scholars of the church, their motives and their accuracy. In particular, the Fifteenth Chapter, which documents the reasons for the rapid spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire, was particularly vilified and resulted in the banning of the book in various countries until quite recently, with Ireland, for example, lifting the ban on sale in the early 1970's.

Despite this official opposition, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire remains surprisingly popular and arguably one of the finest histories in the English language.

Edward Gibbon Quotes

"History is indeed little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind."

"The winds and the waves are always on the side of the ablest navigators."

"Every man who rises above the common level has received two educations: the first from his teachers; the second, more personal and important, from himself."

"All that is human must retrograde if it does not advance."

"Revenge is profitable, gratitude is expensive."

"I was never less alone than when by myself."

On Knowledge and Genius

"Conversation enriches the understanding, but solitude is the school of genius."

"My early and invincible love of reading I would not exchange for all the riches of India."

"The laws of probability, so true in general, so fallacious in particular."

On Society and Government (from The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire)

"The various modes of worship which prevailed in the Roman world were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosopher as equally false; and by the magistrate as equally useful. And thus toleration produced not only mutual indulgence, but even religious concord."

"The principles of a free constitution are irrecoverably lost, when the legislative power is nominated by the executive."